vacuum cleaner apollo

Everyday Tech From Space: How Moon Science Gave Us the DustBuster When people first began using cordless, handheld vacuums to clean up dust and crumbs around the house, few probably saw a connection between their household Hoover and outer space. But, the same technology that helped Apollo astronauts drill for rock samples on the surface of the moon eventually returned to Earth and gave rise to the battery-operated miniature vacuum cleaner. Black & Decker's mini-vac – the DustBuster – was introduced to American consumers in 1979, but the company developed most of the inner workings for the device as the result of a partnership with NASA for the Apollo moon landings between 1963 and 1972. One of the most important tasks for astronauts who landed on the moon was to collect lunar rock and soil samples to bring back for analysis on Earth. While most of these samples could be easily gathered on the surface, scientists also wanted to study the moon's crust by extracting subsurface soil.

To dig out core samples from depths of up to 10 feet (3 meters), the astronauts needed a special drill that could penetrate the sometimes hard lunar surface. The Black & Decker Manufacturing Company, based in Towson, Md., was charged with developing the drill, which needed to be powerful but also compact and lightweight for the journey to the moon. Furthermore, to be most effective, the drill needed to have its own independent power source. This would allow the moonwalkers to be able to wander away from the base and collect samples from a variety of locations without being constrained by the need to use the Lunar Module as a power source. Black & Decker responded with a battery-powered drill with a magnetized motor. And while the device helped Apollo astronauts successfully return samples from the moon, the technology behind it proved to have some valuable uses on Earth as well. In designing a motor that consumed a minimal amount of power, Black & Decker used a special computer program, and their resulting research and development formed the foundation for the company's knowledge base on battery-powered devices.

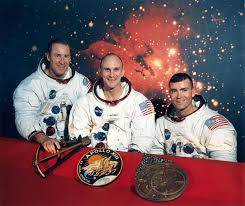

Using the same design parameters as it did for the lunar drill (efficient, powerful, lightweight and compact), Black & Decker produced a line of cordless tools and equipment for the automobile, construction and medical industries, as well as for the average consumer. The DustBuster was marketed as a miniature vacuum cleaner that could be used to clean everyday messes, and suck up dust or crumbs in hard-to-reach places in the car or around the house. Cordless and weighing less than two pounds, the DustBuster was heralded for its convenience. And to think, it all started on the moon. Staff Writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow.Ken Mattingly Explains How the Apollo 13 Movie Differed From Real Life Many astronauts seem to like the Apollo 13 movie, but being technically minded folk they also enjoy pointing out what actually happened during that so-called “successful failure” that landed safely on this day in 1970. Thomas “Ken” Mattingly was supposed to be on that crew, but was yanked at the last minute because he was exposed to the German measles.

The movie shows him wallowing on the couch with a can of beer before hearing of an oxygen tank explosion on board.

hoover vacuum cleaner videoHe then spends most of the movie stuck in a simulator, helping to save the three men on board the spacecraft.

swedish vacuum cleaner cookies Real life wasn’t quite the same as the movie portrayed, the real Mattingly said in a 2001 interview with NASA.

honda outdoor vacuum cleaner For one thing, Mattingly had no assigned role in the rescue as he was a backup crew member. He ended up working in a lot of teams rather than a single project or two. There also were some technical differences between the movie and real life. The “lifeboat” procedures: In the movie, mission controllers huddle in a side room and try to figure out how to stretch the resources of the lunar module — designed to carry only two men for a couple of days — into a four-day lifeboat to support three men.

While this is somewhat true, NASA already had a preliminary lifeboat procedure simulated, Mattingly pointed out. The movie made it appear as though, he said, “we invented a lot of stuff”. Somewhere in an earlier sim [simulation], there had been an occasion to do what they call LM lifeboat, which meant you had to get the crew out of the command module and into the lunar module, and they stayed there. I vaguely remember—when you have a really exciting sim, why, generally everybody knows about it. I vaguely remember that they had come up with a thing that contaminated the atmosphere in the command module, and they had to vent it, and they put the crew into the—there’s some reason that instead of staying in their suits in the command module, they put them in the lunar module while they did this. The carbon dioxide filter: In the movie, as the crew faces a deadly buildup of carbon dioxide, a team in mission control builds a new system on the spot that adapts an originally incompatible filter.

“Well, the real world is better than that,” Mattingly explained, saying there was a simulation for the Apollo 8 mission where a cabin fan was jammed due to a loose screw. The solution that they came up with was that they could make a way to use the vacuum cleaner in the command module with some plastic bags cut up and taped to the lithium hydroxide cartridges and blow through it with a vacuum cleaner. So, having discovered it, they said, “Okay, it’s time for beer.” Well, on 13, someone says, “You remember what we did on that sim? So in nothing short, Joe [Joseph P.] Kerwin showed up, and we talked about “How did you build that bag and what did you do?” … Of course it worked like a gem. Simulating the startup: In the movie, Mattingly spends hours in a simulator putting together the procedures for starting up the cold, dead command module in time to bring the astronauts safely back to Earth. While that is a good way of conveying the mission’s aim to the public, the simulation runs (done by other astronauts, Mattingly said) were more of a verification of already written procedures.